A demon (or daemon, from Ancient Greek, δαίμων daímōn), is a supernatural being from various religions, occultism, literatures, and folklores that is described as something that is not human and, in ordinary (almost universal) usage, malevolent. The original neutral Greek word "daimon" does not carry the negative connotation initially understood by implementation of the Koine (Hellenistic and New Testament Greek) δαιμόνιον (daimonion), and later ascribed to any cognate words sharing the root, originally intended to denote a spirit or spiritual being.

In Ancient Near Eastern religions as well as in the Abrahamic traditions, including ancient and medieval Christian demonology, a demon is considered an "unclean spirit " which may cause demonic possession, to be addressed with an act of exorcism. In Western occultism and Renaissance magic, which grew out of an amalgamation of Greco-Roman magic, Jewish demonology and Christian tradition,[1] a demon is a spiritual entity that may be conjured and controlled. Many of the demons in literature were once fallen angel.

Terminology[]

Ancient Greek daimōn is a word for "spirit" or "divine power", much like the Latin genius or numen. The Merriam-Webster dictionary gives the etymology of the Greek word as from the verb daiesthai "to divide, distribute." The Greek conception of a δαίμων notably appears in the works of Plato, where it describes the divine inspiration of Socrates. To distinguish the classical Greek concept from its later Christian interpretation, it is usually anglicized as either daemon or daimon rather than demon.

The Greek term does not have any connotations of evil or malevolence. In fact, εὐδαιμονία, literally "good-spiritedness", is a term for "happiness". The term first acquired its now-current evil connotations in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible, informed by the mythology of the ancient Semitic religions. This connotation was inherited by the Koine text of the New Testament. The medieval and neo-medieval conception of a "demon" in Western civilization (see the Medieval grimoire called the Ars Goetia) derives seamlessly from the ambient popular culture of Late (Roman) Antiquity. Greco-Roman concepts of daemons that passed into Christian culture are discussed in the entry daemon, though it should be duly noted that the term referred only to a spiritual force, not a malevolent supernatural being. The Hellenistic "daemon" eventually came to include many Semitic and Near Eastern gods as evaluated by Christianity.

The supposed existence of demons is an important concept in many modern religions and occultist traditions. In some present-day cultures, demons are still feared in popular superstition, largely due to their alleged power to possess living creatures. In the contemporary Western occultist tradition (perhaps epitomized by the work of Aleister Crowley), a demon, such as Choronzon, the "Demon of the Abyss", is a useful metaphor for certain inner psychological processes ("inner demons"), though some may also regard it as an objectively real phenomenon. Some scholars[2] believe that large portions of the demonology (see Asmodai) of Judaism, a key influence on Christianity and Islam, originated from a later form of Zoroastrianism, and were transferred to Judaism during the Persian era.

Psychological archetype[]

Psychologist Wilhelm Wundt remarks that "among the activities attributed by myths all over the world to demons, the harmful predominate, so that in popular belief bad demons are clearly older than good ones."[3] Sigmund Freud develops on this idea and claims that the concept of demons was derived from the important relation of the living to the dead: "The fact that demons are always regarded as the spirits of those who have died recently shows better than anything the influence of mourning on the origin of the belief in demons."

M. Scott Peck, an American psychiatrist, wrote two books on the subject, People of the Lie: The Hope For Healing Human Evil[4] and Glimpses of the Devil: A Psychiatrist's Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption.[5]

Peck describes in some detail several cases involving his patients. In People of the Lie: The Hope For Healing Human Evil he gives some identifying characteristics for evil persons whom he classifies as having a character disorder. In Glimpses of the Devil, A Psychiatrist's Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption Peck goes into significant detail describing how he became interested in exorcism in order to debunk the "myth" of possession by evil spirits–only to be convinced otherwise after encountering two cases which did not fit into any category known to psychology or psychiatry. Peck came to the conclusion that possession was a rare phenomenon related to evil. Possessed people are not actually evil; they are doing battle with the forces of evil.[6] His observations on these cases are listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (IV) of the American Psychiatric Association.[7]

Although Peck's earlier work was met with widespread popular acceptance, his work on the topics of evil and possession has generated significant debate and derision. Much was made of his association with (and admiration for) the controversial Malachi Martin, a Roman Catholic priest and a former Jesuit, despite the fact that Peck consistently called Martin a liar and manipulator.[7][8] Other criticisms leveled against Peck include misdiagnoses based upon a lack of knowledge regarding dissociative identity disorder (formerly known as multiple personality disorder), and a claim that he had transgressed the boundaries of professional ethics by attempting to persuade his patients into accepting Christianity.[7]

By tradition[]

Ancient Near East[]

Mesopotamia[]

Human-headed winged bull, otherwise known as a Šedu

In Chaldean mythology the seven evil deities were known as shedu, meaning storm-demons. They were represented in winged bull form, derived from the colossal bulls used as protective genii of royal palaces, the name "shed" assumed also the meaning of a propitious genius in Babylonian magic literature.[9]

It was from Chaldea that the name "shedu" came to the Israelites, and so the writers of the Tanach applied the word as a dylogism to the Canaanite deities in the two passages quoted. They also spoke of "the destroyer" (Exodus xii. 23) as a Lord who will "strike down the Egyptians." In II Samuel xxiv; 16 and II Chronicles xxi. 15 the pestilence-dealing angel, that is spirit, called "the destroying angel" (compare "the angel of the Lord" in II Kings xix. 35; Isaiah xxxvii. 36), because, although they are angels, these "messengers" (Psalms lxxviii. 49; A. V. "angels") do only the bidding of God; they are the agents of His divine wrath.

There are indications that popular Hebrew mythology ascribed to the demons a certain independence, a malevolent character of their own, because they are believed to come forth, not from the heavenly abode of God, but from the nether world.[10]

In the Hebrew tradition demons were workers of harm. To them were ascribed the various diseases, particularly such as affect the brain and the inner parts. Hence there was a fear of "Shabriri" (lit. "dazzling glare"), the demon of blindness, who rests on uncovered water at night and strikes those with blindness who drink of it;[11] also mentioned were the spirit of catalepsy and the spirit of headache, the demon of epilepsy, and the spirit of nightmare.

These demons were supposed to enter the body and cause the disease while overwhelming or "seizing" the victim (hence "seizure"). To cure such diseases it was necessary to draw out the evil demons by certain incantations and talismanic performances, in which the Essenes excelled. Josephus, who speaks of demons as "spirits of the wicked which enter into men that are alive and kill them", but which can be driven out by a certain root,[12] witnessed such a performance in the presence of the Emperor Vespasian,[13] and ascribed its origin to King Solomon.

Ancient Arabia[]

Pre-Islamic mythology does not discriminate between gods and demons. The jinn are considered as divinities of inferior rank, having many human attributes: they eat, drink, and procreate their kind, sometimes in conjunction with human beings. The jinn smell and lick things, and have a liking for remnants of food. In eating they use the left hand. Usually they haunt waste and deserted places, especially the thickets where wild beasts gather. Cemeteries and dirty places are also favorite abodes. When appearing to man, jinn sometimes assume the forms of beasts and sometimes those of men.

Generally, jinn are peaceable and well disposed toward men. Many a pre-Islamic poet was believed to have been inspired by good jinn, but there are also evil jinn, who contrive to injure men.

Hebrew Bible[]

Lilith, by John Collier, 1892

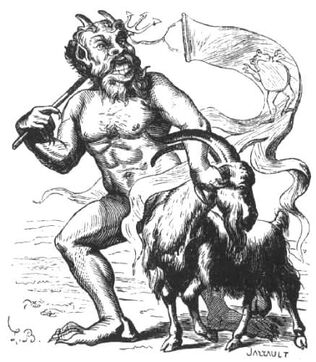

Those in the Hebrew Bible are of two classes, the se'irim and the shedim.Template:Citation needed The se'irim ("hairy beings"), to which some Israelites offered sacrifices in the open fields, are satyr-like creatures, described as dancing in the wilderness,[14] and which are identical with the jinn, such as Dantalion, the 71st spirit of Solomon.

Some benevolent shedim were used in kabbalistic ceremonies (as with the golem of Rabbi Yehuda Loevy), and malevolent shedim (mazikin, from the root meaning "to damage") were often credited with possession. Similarly, a shed might inhabit an otherwise inanimate statue.

Judaism[]

- Main article: Aggadah

In some rabbinic sources, the demons were believed to be under the dominion of a king or chief, either Asmodai[15] or, in the older Haggadah, Samael ("the angel of death"), who kills by his deadly poison, and is called "chief of the devils". Occasionally a demon is called "satan": "Stand not in the way of an ox when coming from the pasture, for Satan dances between his horns".[16]

Demonology never became an essential feature of Jewish theology.Template:Citation needed The reality of demons was never questioned by the Talmudists and late rabbis; most accepted their existence as a fact. Nor did most of the medieval thinkers question their reality. Only rationalists like Maimonides and Abraham ibn Ezra, clearly denied their existence. Their point of view eventually became the mainstream Jewish understanding.

Rabbinical demonology has three classes of demons, though they are scarcely separable one from another. There were the shedim, the Template:Unicode ("harmers"), and the Template:Unicode ("spirits"). Besides these there were lilin ("night spirits"), Template:Unicode ("shade", or "evening spirits"), Template:Unicode ("midday spirits"), and Template:Unicode ("morning spirits"), as well as the "demons that bring famine" and "such as cause storm and earthquake" (Targ. Yer. to Deuteronomy xxxii. 24 and Numbers vi. 24; Targ. to Cant. iii. 8, iv. 6; Eccl. ii. 5; Ps. xci. 5, 6.)[17]

Christian demonology[]

- Main article: Christian demonology

Death and the Miser (detail), a Hieronymus Bosch painting, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

"Demon" has a number of meanings, all related to the idea of a spirit that inhabited a place, or that accompanied a person. Whether such a daemon was benevolent or malevolent, the Greek word meant something different from the later medieval notions of 'demon', and scholars debate the time in which first century usage by Jews and Christians in its original Greek sense became transformed to the later medieval sense. Some denominations asserting Christian faith also include, exclusively or otherwise, fallen angels as de facto demons; this definition also covers the "sons of God" described in Genesis who abandoned their posts in heaven to mate with human women on Earth before the Deluge.[18]

In the Gospels, particularly the Gospel of Mark, Jesus casts out many demons, or evil spirits, from those who are afflicted with various ailments. Jesus is far superior to the power of demons over the beings that they inhabit, and he is able to free these victims by commanding and casting out the demons, by binding them, and forbidding them to return. Jesus also lends this power to some of his disciples, who rejoice at their new found ability to cast out all demons.[19] The demons are cast out by the pronunciation of a name according to Template:Bibleverse, some groups insisting the original pronunciation of the name Jesus and pure form of worship be used i.e. Yahshua / Joshua meaning "Yahweh is salvation". The demons or unclean spirits themselves often recognize Jesus as the Messiah, according to the accounts. In Matthew 12:43, Jesus teaches that when they are driven from a human, they go through dry places as disembodied spirits seeking rest, although on another occasion, he sends them into a herd of swine.

By way of contrast, in the book of Acts a group of Judaistic exorcists known as the sons of Sceva try to cast out a very powerful spirit without believing in or knowing Jesus, but fail with disastrous consequences. However Jesus himself never fails to vanquish a demon, no matter how powerful (see the account of the demon-possessed man at Gerasim), and even defeats Satan in the wilderness (see Gospel of Matthew).

There is a description in the Book of Revelation 12:7-17 of a battle between God's army and Satan's followers, and their subsequent expulsion from Heaven to Earth to persecute humans — although this event is related as being foretold and taking place in the future. In Luke 10:18 it is mentioned that a power granted by Jesus to cast out demons made Satan "fall like lightning from heaven."

Augustine of Hippo's reading of Apuleius, in City of God (Bk. IX, ch.11) is ambiguous as to whether daemons had become 'demonized' by the early 5th century:

- "He [Apulieus] also states that the blessed are called in Greek eudaimones, because they are good souls, that is to say, good demons, confirming his opinion that the souls of men are demons.[20]

The contemporary Roman Catholic Church unequivocally teaches that angels and demons are real personal beings, not just symbolic devices. The Catholic Church has a cadre of officially sanctioned exorcists which perform many exorcisms each year. The exorcists of the Catholic Church teach that demons attack humans continually but that afflicted persons can be effectively healed and protected either by the formal rite of exorcism, authorized to be performed only by bishops and those they designate, or by prayers of deliverance which any Christian can offer for themselves or others.[21]

Building upon the few references to daemons in the New Testament, especially the visionary poetry of the Apocalypse of John, Christian writers of apocrypha from the 2nd century onwards created a more complicated tapestry of beliefs about "demons" that was largely independent of Christian scripture.

At various times in Christian history, attempts have been made to classify these beings according to various proposed demonic hierarchies.

According to most Christian demonology demons will be eternally punished and never reconcile with God. Other theories postulate a Universal reconciliation, in which Satan, the fallen angels, and the souls of the dead that were condemned to Hell are reconciled with God. This doctrine is today often associated with the Unification Church. Origen, Jerome and Gregory of Nyssa also mentioned this possibility.

In contemporary Christianity, demons are generally considered to be angels who fell from grace by rebelling against God. However, other schools of thoughtTemplate:Who in Christianity or Judaism teach that demons, or evil spirits, are a result of the sexual relationships between fallen angels and human women.[18] When these hybrids (Nephilim) died they left behind disembodied spirits that "roam the earth in search of rest" (Luke 11:24).Template:Citation needed Many non-canonical historical texts describe in detail these unions and the consequences thereof. This belief is repeated in other major ancient religions and mythologies. Christians who reject this view do so by ascribing the description of "Sons of God" in Genesis 6 to be the sons of Seth (one of Adam's sons).

There are some who say that the sin of the angels was pride and disobedience, these being the sins that caused Satan's downfall (Ezek. 28). If this be the true view, then we are to understand the words, "estate" or "principality" in Deuteronomy 32:8 and Jude 6 ("And the angels which kept not their first estate, but left their own habitation, he hath reserved in everlasting chains under darkness unto the judgment of the great day.") as indicating that instead of being satisfied with the dignity once for all assigned to them under the Son of God, they aspired higher.

Renaissance demonology[]

Although no canon of Renaissance demonology exist, the interest in classic Greco-Roman culture, philosophy, science and Greek and Roman mythology also created a playground for experience with, what was supposed to be a Pre-Christian religious practice. Most notably found in popular culture like the legend of Faust.

Islam[]

The Majlis al Jinn cave in Oman, literally "Meeting place of the Jinn".

Template:See also

Islam recognizes the existence of the jinn, which are sentient beings with free will that can co-exist with humans and are not all evil as demons are described in Christianity. The creation of Jinnkind preceded that of mankind. They exist in what is known as the Al-Ghaib (unseen or unknown) realm or world, they have the ability to see us but we can not see them. Angels also exist in this realm, as well as the human soul (hence why it can not be seen leaving the human body in death). The Jinns are made from the smokeless flame of fire and both angels and the human soul are made from light, whilst the human body is made from clay. Though this "fire" and "light" is beyond matter, whatever exists in this realm is made from matter. In Islam, the evil Jinns are referred to as the shayātīn, or devils, and Iblis (Satan) is their chief. Iblis was one of the first Jinn (he is not considered an Angel in Islamic Cultures) who disobeyed Allah (God) and did not bow down before Adam.

Angels are servants of Allah who do not possess any freewill, whilst Jinnkind and mankind do. It was because Adam possessed freewill and the ability to choose (to do either good or bad) but instead chose to submit his will to the will of Allah, that Allah loved him so; so much so that mankind's status was elevated higher than that of Angelkind because the Angels have no choice but to serve Allah. According to the Qur'an, when Allah created Adam from clay, all the angels and Iblis himself were ordered to bow before Adam. Iblis became very jealous and disobeyed Allah, holding that jinns were the superior creation, as they were made of fire, while humans were made of clay.

Adam was the first prophet and deputy of the human race, and as such was the greatest creation of Allah. Iblis could not stand this, and refused to acknowledge a creature made of "clay" (matter). Allah, thus, condemned Iblis to be punished in the hellfire. But Iblis asked for respite until the last day (judgement day) and this is when the devil and God made a pact and the devil claimed that if he was given the chance, he could make mankind fall and vowed that one day he would even have Allah's beloved creation (mankind) denying the very existence of their creator, to which Allah's agreed, but warned that he and all who would follow him in evil would be punished in hell. Allah also stated that Iblis would only be able to mislead those who have forsaken Allah and not the righteous believers.

Adam and Eve (Hawwa in Arabic) were both together misled by Iblis into eating the forbidden fruit, and consequently fell from the garden of Eden (allegorical) into a state of degeneration.

Jinns are not the "genies" of modern lore. Like man, there are good and bad, believers and non-believers amongst them. The evil Jinns have been known to possess human beings or enter a humans life in order to hinder it. Their actions are similar to that of a poltergeist in Western understanding. Contrary to the evil Jinns, the good Jinns (servants of good) and can enter a human life in order to help them in numerous ways. The entry to our realm is forbidden without Allah permission. Both the Angels and Jinns can enter in the form of a human being or an animal. As Angels do not posses free will and the good Jinn are obedient, they never enter without Allah's permission. However, the same cannot be said for the evil Jinn who enter as they will and have been known to take the form of many animals (especially black Dogs and Snakes) and human beings.

Hinduism[]

Hindu mythology includes numerous varieties of spirits that might be classified as demons, including Vetalas, Bhutas and Pishachas. Often Rakshasas and Asuras are taken to mean demons.

Asuras[]

Asura in Kōfuku-ji, Nara, 734, Japanese

The Army of Super Creatures - from The Sougandhika Parinaya Manuscript (1821 CE)

Originally, Asura, in the earliest hymns of the Rig Veda, meant any supernatural spirit, both good and bad. Since the /s/ of the Indic linguistic branch is cognate with the /h/ of the Early Iranian languages, the word Asura, representing a category of celestial beings, became the word Ahura (Mazda), the Supreme God of the monotheistic Zoroastrians. Ancient Hinduism tells that Devas and Asuras are half-brothers, sons of the same father Kasyapa; but some of the devas, like Varuna, are also named Asuras. But much later at puranic age Asura (also Rakshasa) came to exclusively mean any of a race of anthropomorphic, powerful, possibly evil beings. All words such as Asura, Daitya (lit., sons of the mother "Diti"), Rakshasa (lit. from "harm to be guarded against") are incorrectly translated into English as demon.

Asuras do accept and worship the Gods, particularly the Hindu triumvirate; some of the rakshasas like Ravana and Mahabali are exemplary devotees. Often the strife between the asuras and the devas is simply a political one: devas are the ordained maintainers of the realms with power (and immortality) accorded to them by the gods and asuras ever strive to attain both. Asuras usually attain or enhance their supernatural powers through penance to gods and waging war on devas using powers thus attained. Unlike Christian notion of demons, asuras are not the cause of the evil and unhappiness in mankind (unhappiness in humans, according to Hinduism is by one's own actions (Karma) and/or due to the continued ignorance of Brahman, the unchanging reality. Asuras, if any, are cogs in the wheel of Karma); they are not fundamentally against the Gods, nor do they tempt humans to fall. In fact, asuras, much like devas, do worship the Gods of Hinduism: many Asuras are said to have been granted boons from one of the members of the Hindu trinity, viz., Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva when the latter had been appeased from their penances. This is markedly different from the traditional Western notions of demons as a rival army of God. In Hindu mythology, pious, highly enlightened asuras, like Prahlada and Vibheeshana, are not at all uncommon. Prahlada even said to have secured enlightenment to his entire lineage (of asuras). All Asuras, unlike the devas, are said to have born mortals (though they ever strive to become immortal). Many people metaphorically interpret asuras as manifestations of the ignoble passions in human mind and as a symbolic device. There were also cases of power-hungry asuras challenging various aspects of Gods, but only to be defeated eventually and seek forgiveness—see Surapadman, Narakasura.

Evil spirits[]

Hinduism advocates the theory of reincarnation and transmigration of souls according to one's Karma. Souls (Atman) of the dead are adjudged by the Yama and are accorded various purging punishments before being reborn. Humans that have committed extraordinary wrongs are condemned to roam as lonely, often evil, spirits for a length of time before being reborn. Many kinds of such spirits (Vetalas, Pishachas, Bhūta) are recognized in the later Hindu texts. These beings, in a limited sense, can be called demons.

Bahá'í Faith[]

In the Bahá'í Faith, demons are not regarded as independent evil spirits as they are in some faiths. All evil spirits described in various faith traditions such as Satan, fallen angels, demons and jinns are metaphors for the base character traits a human being may acquire and manifest when he turns away from God and follows his lower nature. Belief in the existence of ghosts and earthbound spirits is rejected and considered to be the product of superstition.[22]

See also[]

Template:Multicol

- Daemon (classical mythology)

- Archdemon

- Classification of demons

- Christian demonology

- Demonic possession

- Demonolatry

Template:Multicol-break

- Fiend

- Folk devil

- Imp

- List of theological demons

- List of fictional demons

- Names of the demons

Template:Multicol-break

- Oni

- Saint Michael

- Satanism

- Spiritual warfare

- Vampire

- Yaoguai

Template:Multicol-end

Notes[]

- ↑ See, for example, the course synopsis and bibliography for ""Magic, Science, Religion: The Development of the Western Esoteric Traditions", at Central European University, Budapest

- ↑ Boyce, 1987; Black and Rowley, 1987; Duchesne-Guillemin, 1988.

- ↑ Freud (1950, 65), quoting Wundt (1906, 129).

- ↑ People of the Lie: The Hope For Healing Human Evil (1983)

- ↑ Glimpses of the Devil: A Psychiatrist's Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption (2005).

- ↑ The exorcist, an interview with M. Scott Peck by Rebecca Traister published in Salon

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 The devil you know, a commentary on Glimpses of the Devil by Richard Woods

- ↑ The Patient Is the Exorcist, an interview with M. Scott Peck by Laura Sheahen

- ↑ See Delitzsch, Assyrisches Handwörterbuch. pp. 60, 253, 261, 646; Jensen, Assyr.-Babyl. Mythen und Epen, 1900, p. 453; Archibald Sayce, l.c. pp. 441, 450, 463; Lenormant, l.c. pp. 48-51.

- ↑ compare Isaiah xxxviii. 11 with Job xiv. 13; Psalms xvi. 10, xlix. 16, cxxxix. 8

- ↑ Pesachim 112a; Avodah Zarah 12b

- ↑ Bellum Judaeorum vii. 6, § 3

- ↑ "Antiquities" viii. 2, § 5

- ↑ Isaiah 13:21, 34:14

- ↑ Targ. to Eccl. i. 13; Pes. 110a; Yer. Shek. 49b

- ↑ Pes. 112b; compare B. Ḳ. 21a

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Genesis 6:2, 4, also see Nephilim

- ↑ Template:Bibleverse

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link

- ↑ Template:Cite book

References[]

- Template:Cite book

- Wundt, W. (1906). Mythus und Religion, Teil II (Völkerpsychologie, Band II). Leipzig.

- Castaneda, Carlos (1998). The Active Side of Infinity. HarperCollins NY ISBN 978-0-06-019220-4

Further reading[]

- Template:Cite book

External links[]

Template:Wiktionary Template:Wiktionary

- Catechism of the Catholic Church: Hyperlinked references to demons in the online Catechism of the Catholic Church

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Demonology

- Profile of William Bradshaw, American demonologist Riverfront Times, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. August 2008.

am:ጋኔን

bg:Демон

cs:Démon

da:Dæmon

de:Dämon

et:Deemon

es:Demonio

eo:Demono

fr:Démon (esprit)

ko:악령

hr:Demon

io:Demono

id:Demon

it:Demone

he:שד (מיתולוגיה)

jv:Démon

ka:დემონი

la:Daemon

lv:Dēmons

lt:Demonas

hu:Démon

mk:Демон

mdf:Демон

nah:Tzitzimītl

nl:Demon

ja:悪霊

no:Demon

nn:Demon

pl:Demon

pt:Demónio

ru:Демон

scn:Dimoniu

simple:Demon

sk:Démon

sl:Demon

szl:Dymůn

sr:Демон

sh:Demon

fi:Demoni

sv:Demon

tl:Demonyo

tr:Demon

uk:Демон

vi:Quỷ

zh:邪靈